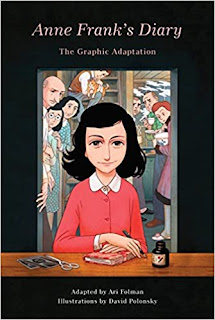

what i'm reading: graphic adaptation of anne frank's diary

Diary of a Young Girl, by Anne Frank, is many things to many people.

It's the most widely read and recognizable Holocaust narrative.

It's one of the most common ways to teach young people about the Holocaust specifically and genocidal in general.

It's a book for all ages. I read it as a child, as a teen, and as an adult, and I understood it on different levels at different times of my life -- and that's probably a common experience. If you haven't re-read the Diary as an adult, I highly recommend it.

The Diary has been translated into 70 languages and more than 25 million copies have been printed worldwide. It continues to be read in schools all over the world. This is partly because the first-person account personalizes the experience, makes it relatable, in a way that conventional histories cannot. But I believe the impact of the Diary endures because Anne was such a talented writer.

This fact is often overlooked in discussions of the Diary, overshadowed by the experiences Anne wrote about and the extremity of her living situation. You will often see reviewers mention "Anne's voice" -- and there's no doubt that Anne's appealing personality adds to the compelling nature of the Diary. But the girl who was hiding in that Amsterdam attic was a talented writer, and I believe that fact, more than anything else, has made the Diary transcend culture, time, and place, and is the central reason it endures.

Anne was a writer. Proof of that is in the Diary itself: the more she wrote, the better her writing became. She was becoming a writer, as all writers are, always. It's obvious that at some point, Anne realized her diary might be shared with the outside world, and she upped her game. Anne dreamed of becoming a famous writer -- a dream that came true, without her.

The graphic adaptation of the Diary does many things well, but also strains against the limits of the form. To expand on this, I'm doing something here that I rarely do: quoting from other reviews.

What I really liked

David Polonsky's illustrations are gorgeous -- lavish, rich in detail, suffused with emotion. Ari Folman uses the graphic novel form to its utmost advantage.

It's disappointing when graphic novel creators use illustrations as they would be used in a conventional novel -- illustrating what's already in the text -- rather than as an integral part of the story itself, moving the story forward in time and meaning.

As Ruth Franklin wrote in this New York Times review,

The graphic adaptation beautifully captures Anne's personality and her voice -- not just her longing and frustration, which is more widely known, but her sarcasm and her sardonic wit. Parts of the Diary are funny, because Anne was funny. We shouldn't be afraid of that humour. Laughing with Anne is not laughing at the Holocaust. If anything, the humour only deepens our understanding of her tragedy, because it makes more real to us.

What didn't work for me

In The Atlantic, Stav Ziv notes that "the shortcomings of the adaptation are illuminating in their way, and underscore what makes the original so potent". I have to agree.

It's the most widely read and recognizable Holocaust narrative.

It's one of the most common ways to teach young people about the Holocaust specifically and genocidal in general.

It's a book for all ages. I read it as a child, as a teen, and as an adult, and I understood it on different levels at different times of my life -- and that's probably a common experience. If you haven't re-read the Diary as an adult, I highly recommend it.

The Diary has been translated into 70 languages and more than 25 million copies have been printed worldwide. It continues to be read in schools all over the world. This is partly because the first-person account personalizes the experience, makes it relatable, in a way that conventional histories cannot. But I believe the impact of the Diary endures because Anne was such a talented writer.

This fact is often overlooked in discussions of the Diary, overshadowed by the experiences Anne wrote about and the extremity of her living situation. You will often see reviewers mention "Anne's voice" -- and there's no doubt that Anne's appealing personality adds to the compelling nature of the Diary. But the girl who was hiding in that Amsterdam attic was a talented writer, and I believe that fact, more than anything else, has made the Diary transcend culture, time, and place, and is the central reason it endures.

Anne was a writer. Proof of that is in the Diary itself: the more she wrote, the better her writing became. She was becoming a writer, as all writers are, always. It's obvious that at some point, Anne realized her diary might be shared with the outside world, and she upped her game. Anne dreamed of becoming a famous writer -- a dream that came true, without her.

The graphic adaptation of the Diary does many things well, but also strains against the limits of the form. To expand on this, I'm doing something here that I rarely do: quoting from other reviews.

What I really liked

David Polonsky's illustrations are gorgeous -- lavish, rich in detail, suffused with emotion. Ari Folman uses the graphic novel form to its utmost advantage.

It's disappointing when graphic novel creators use illustrations as they would be used in a conventional novel -- illustrating what's already in the text -- rather than as an integral part of the story itself, moving the story forward in time and meaning.

As Ruth Franklin wrote in this New York Times review,

As Folman acknowledges in an adapter’s note, the text, preserved in its entirety, would have resulted in a graphic novel of 3,500 pages. At times he reproduces whole entries verbatim, but more often he diverges freely from the original, collapsing multiple entries onto a single page and replacing Anne’s droll commentary with more accessible (and often more dramatic) language. Polonsky’s illustrations, richly detailed and sensitively rendered, work marvelously to fill in the gaps, allowing an image or a facial expression to stand in for the missing text and also providing context about Anne’s historical circumstances that is, for obvious reasons, absent from the original. The tightly packed panels that result, in which a line or two adapted from the “Diary” might be juxtaposed with a bit of invented dialogue between the Annex inhabitants or a dream vision of Anne’s, do wonders at fitting complex emotions and ideas into a tiny space — a metaphor for the Secret Annex itself.Here are a few examples of the skillful and inventive artwork.

|

| Anne imagines her future. |

The graphic adaptation beautifully captures Anne's personality and her voice -- not just her longing and frustration, which is more widely known, but her sarcasm and her sardonic wit. Parts of the Diary are funny, because Anne was funny. We shouldn't be afraid of that humour. Laughing with Anne is not laughing at the Holocaust. If anything, the humour only deepens our understanding of her tragedy, because it makes more real to us.

What didn't work for me

In The Atlantic, Stav Ziv notes that "the shortcomings of the adaptation are illuminating in their way, and underscore what makes the original so potent". I have to agree.

The difference between the two versions, however, is that by this point in the diary, you've been in her head for so long that her extinguished voice and sudden disappearance crush you with the weight of the world. You can imagine heavy boots on the stairs, pounding on the bookcase, and cruel orders spewed at the shocked residents. This scene isn't described in detail in either version. In fact, the afterwords are virtually identical. But the diary itself sets the reader up to fill in the horrifying blanks in a way the adaptation does not. They weren't coming for an unknowable character in hiding. They were coming for Frank.For me, it comes down to this: I loved reading this book, and I hope it moves readers to search out and read the original. If this was to be a reader's only contact with The Diary of Anne Frank, I would be both relieved and disappointed. I recommend this version without hesitation -- but I hope you will re-read the original, too.

It's not that Folman and Polonsky haven't added a valuable interpretation. They have. The volume contains some stunning and poetic drawings, such as a two-page spread that visualizes a passage in which the diarist describes "the eight of us in the Annex as if we were a patch of blue sky surrounded by menacing black clouds" and "in our desperate search for a way out we keep bumping into each other." But those images are poignant complements to Frank's words, not sufficient replacements. To this point, Folman wrote in the adapter's note that he had "grave reservations" editing "while still being faithful to the entire work." On the whole, the story becomes shorter, neater, and more naive. That might make sense if the adaptation were a primer geared toward children who aren't ready to tackle the diary yet, but the inclusion of entries on sex and Frank's lesson on the female anatomy indicates otherwise.

The point is also not that illustrations or graphic novels are less suited to tell stories of the Holocaust. Those mediums and so many others, including artificial intelligence and virtual reality, offer opportunities to experiment with new ways to share narratives that humanize and resonate—all the more crucial as we get further from the history and those who lived it. But the format should be tailored to the story, and in the case of a story that power lies squarely in the quality of the writing and the vividness of a teenager's thoughts, the diary provides depth that is hard to replicate in other versions.

The movies, plays, and graphic adaptations that Frank's diary inspired are entry points, thought provokers, or conversation starters, not substitutes. The most promising way to keep her story in the forefront of our mind is to keep reading her diary, but also to continue allowing the original source to spark a broad range of retellings and interpretive works of art that might highlight different aspects and reach new audiences. All together, they foster discussion and remind readers of the smart, vivacious, and complicated girl who went into hiding at 13 and died at 15.

The graphic adaptation does contain long sections of Frank's last entries—the ones that make it so distressing to see her account end as abruptly as it does. But the omissions leading up to them soften the blow. More than any particular fact or event, the graphic version is missing the sense of familiarity that slowly builds, more strongly and deeply than you realize, until the moment that this friend, this stand-in for you, confronts the thing she'd feared for so long: the moment that stole her fantasies of her life "after the war" out from under her. The last pages of the adaptation feel like the end of a story, not the end of a life.

Comments

Post a Comment