listening to joni: #10: mingus

Mingus, 1979

Mingus is unique in Joni's work, in that she wrote lyrics to someone else's instrumental music. Four of the six tracks on Mingus were written collaboratively by Joni and Charles Mingus.

Charles Mingus was a jazz composer and band leader. He was enormously influential, and anyone following contemporary jazz music would have known his work. But it's doubtful whether in 1979 most Joni Mitchell fans even knew his name, let alone recognized his music.

In the late 1970s, Mingus had ALS and was failing physically. He reached out to Joni, and they began a long-distance friendship. After about a year, he asked Joni to write lyrics to a group of songs he had composed.

The full story of how the collaboration began is more complex, but it wasn't known at the time. Mingus died before the album was finished, although he did hear finished versions of most of the songs.

Mingus is another step on the jazz path Joni began with Court and Spark, and which became a greater part of her music with each album since. It turned out to be Joni's last jazz album.

Mingus will never be my favourite Joni album, but I do like it, and of course I admire Joni's willingness to follow her musical star wherever it led her. When I listen to this album, I find myself focusing almost exclusively on Joni's voice and the lyrics, and almost not hearing the other instruments, keeping them well in the background.

The music behind the lyrics is abstract and challenging. There's a wash of soft sounds, over-buzzy echoing bass lines, and Joni's own guitar, unmistakable, but more restrained and minimalist than we've ever heard her before. I listen to a lot of jazz, but this kind of abstract fusion is not my thing.

The most unusual piece on the album is one of the two that Joni composed: "The Wolf That Lives In Lindsey". On a blog called "Ethan's Greats," I found this wonderful description.

The song is about racism – the racism Young faced as a musician, and about the anger he encountered when he married a white woman.

Sue Graham Mingus, Charles Mingus' wife, was also white. Joni herself was harshly criticized – and accused of racism – for following her musical journey into supposedly Black territory.

Another song on Mingus that I like is "The Dry Cleaner from Des Moines". The singer meets the Iowa man in a casino, where he is cleaning up.

Mingus also includes interludes that the album cover calls "raps" – five short sound clips of Charles Mingus talking and joking around with the session musicians. These can be unnecessary distractions or amusing insider views, depending on how you're listening. They were not planned. Sue Mingus made the session tapes available to Joni and she decided to pull out clips for the album. They are the last recordings Charles Mingus made.

Bad critic comment of the album

I had remembered this album being very badly received, and some bizarre accusations being hurled at Joni. When I look for that now, however, I find very little of it. Most of the reviews and features collected here on the jonimitchell.com are very positive.

I don't know if those stories just aren't online, or if I'm misremembering or unknowingly exaggerating what I read at the time.

What I remember is Joni accused of what is now called cultural appropriation: Joni was "trying to be black". She was trashed for being a jazz novice and dilettante – a kind of "how dare she" collaborate with a Jazz Great like Mingus.

These are just about the stupidest things you can say about a musician – about any artist – and even stupider when we consider that Mingus reached out to Joni, and not the other way around. (Although if she had reached out to him, or any other musician, there would be absolutely nothing wrong with that.)

There are many tributes to this album online, celebrating both its music and its lyrics. Cameron Crowe did this wonderful interview in Rolling Stone (I remember reading it in real time) (really, I do), and a few months later, the album was panned in the same venue.

The most idiotic critic comment I found was in a university newspaper. I normally don't trash novice writers, but the evidence here is too good to pass up. I'm also including it because it's typical of what I remember reading at the time.

The album cover

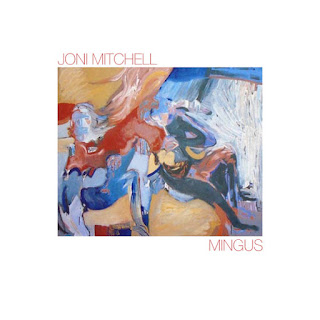

If you like Joni's painting, the Mingus cover art is a treat – four pieces on this one album.

On the front cover, there's an abstract expressionist painting, and if you look closely, you'll see a figure in a wheelchair (from behind), and a long-legged, female figure, sitting, possibly at a piano, her arm raised, hand on head. Interestingly, the painting is not the full cover. The painting is in the centre of the cover, framed by white space, with the album and artist's names above and below. This serves to make the cover more minimalist – which is what you'll find inside, music that is abstract and minimal.

Inside, there's an expressionist portrait of Mingus as big, clumsy, immobile, possibly paralyzed. But he also seems deified, like some of kind of ancient god descending from the heavens.

Also inside, there's another slightly abstract, slightly cubist portrait of Mingus, with Joni beside and behind him, smiling, but unseeing. It's a painted version of a lovely photo that you can see here.

On the back cover, Joni has painted Charles Mingus in his wheelchair, from behind, on a front porch or veranda with a sweeping view. It might be a sad and lonely picture, or perhaps just contemplative.

Cacti or stockings?

Naturally there are no cactus or stockings in this album, as the lyrics are not about Joni. I wonder, is the age of cacti and stockings behind us? Does she do that on any of the later albums? We shall see.

Now it can be told

David Yaffe, in Reckless Daughter: A Portrait of Joni Mitchell, revealed the genesis of the Mingus-Mitchell collaboration. This excerpt, published in Jazz Times, credits Sue Graham Mingus – Mingus's wife, a record producer, band manager, and former editor – with the idea. She was casting around for a fitting final project for Mingus, an outsize talent who was dying. It seems more marketing decision than a musician's desire to connect.

This bit has stayed with me.

For the "other musicians" section on this album, I'm using Joni's own liner notes.

Mingus is unique in Joni's work, in that she wrote lyrics to someone else's instrumental music. Four of the six tracks on Mingus were written collaboratively by Joni and Charles Mingus.

Charles Mingus was a jazz composer and band leader. He was enormously influential, and anyone following contemporary jazz music would have known his work. But it's doubtful whether in 1979 most Joni Mitchell fans even knew his name, let alone recognized his music.

In the late 1970s, Mingus had ALS and was failing physically. He reached out to Joni, and they began a long-distance friendship. After about a year, he asked Joni to write lyrics to a group of songs he had composed.

The full story of how the collaboration began is more complex, but it wasn't known at the time. Mingus died before the album was finished, although he did hear finished versions of most of the songs.

Mingus is another step on the jazz path Joni began with Court and Spark, and which became a greater part of her music with each album since. It turned out to be Joni's last jazz album.

Mingus will never be my favourite Joni album, but I do like it, and of course I admire Joni's willingness to follow her musical star wherever it led her. When I listen to this album, I find myself focusing almost exclusively on Joni's voice and the lyrics, and almost not hearing the other instruments, keeping them well in the background.

The music behind the lyrics is abstract and challenging. There's a wash of soft sounds, over-buzzy echoing bass lines, and Joni's own guitar, unmistakable, but more restrained and minimalist than we've ever heard her before. I listen to a lot of jazz, but this kind of abstract fusion is not my thing.

The most unusual piece on the album is one of the two that Joni composed: "The Wolf That Lives In Lindsey". On a blog called "Ethan's Greats," I found this wonderful description.

"The Wolf That Lives in Lindsey" is a battle between furious plucks of a bass, playing at a different tune of the acoustic guitar that plays high and low at once, and the hand drums that beat, well, to their own drum, appropriately. Mitchell, though past the age in which a listener could tell her voice was going, soars to old vocal heights – "Of the darkness in men's minds/ what can you say/ that wasn't marked by history," she ponders and sort of tells a story of the men and their darknesses, wandering the streets, as well as of Lindsey, who finds her own darkness expressed within. There is one more instrument combining here as well – howls of wolves, used as a composition that actually complements all the desultory elements. "The Wolf" isn't the sort of song that you can pull out of a jazz record and turn into a standard, but it is one that takes hold reflecting the uncertainty and mystery of the world and wanders gorgeously with its consciousness into the dark. The guitar, the howls, the voice, the deep pluck of that bass awaken something – fear and sadness living simultaneously with sensuality.For me, the most memorable song on Mingus is a jazz standard, "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat," written by Charles Mingus in 1959, about the late, great Lester Young. In her lyrics, written 20 years after Young's death, Joni doesn't pretend she knew Lester Young. She doesn't try to write his eulogy. She boldly states her perspective in the opening line.

When Charlie speaks of Lester...That line says so much. Joni has only recently become part of the jazz scene. She's not presuming or pretending. She's telling you about a Lester Young that she knows through Charles Mingus.

|

| Back Cover |

Sue Graham Mingus, Charles Mingus' wife, was also white. Joni herself was harshly criticized – and accused of racism – for following her musical journey into supposedly Black territory.

...When the bandstands had a thousand waysThe song also includes this beautiful New York City moment.

Of refusing a black man admission

Black musician

In those days they put him in an

Underdog position

Cellars and chitlins'

When Lester took him a wife

Arm and arm went black and white

And some saw red

And drove them from their hotel bed

Love is never easy

It's short of the hope we have for happiness

Bright and sweet

Love is never easy street!

We came up from the subwayIn "Sweet Sucker Dance," Joni revisits a familiar theme in yet another new way. She wonders if she can let herself do the "sweet sucker dance" – fall in love – again. She admits she "almost closed the door" because "the shadows had their way".

On the music midnight makes

To Charlie's bass and Lester's saxophone

In taxi horns and brakes

|

| Inside Cover |

They'd turn my heart against youJoni asks, "Am I a sucker to love you?" The song answers the question Joni-style. While it may be sad to think that falling in love is a "sucker dance," it's also sweet, and it's inevitable, and it's part of life, because sometimes the shadows have had their way.

Since I was fool enough

To find romance

I'm trying to convince myself

This is just a dance

We move in measures

Through loves' changing faces

Needy and nonchalant

Greedy and gracious

Through petty dismissals

And grand embraces

Like it was only a dance

We are survivors

Some get broken

Some get mended

Some can't surrender

They're too well defended

Some get lucky

Some are blessed

And some pretend

This is only a dance

We're dancing fools

You and me

Tonight it's a dance of insecurity

It's my solo

While you're away

And shadows have the saddest thing to say

Another song on Mingus that I like is "The Dry Cleaner from Des Moines". The singer meets the Iowa man in a casino, where he is cleaning up.

He got three orangesI read this as a lighthearted take on the random chance of everything. Perhaps Mingus, dying while possessing the full force of his talent, was feeling the random chance of the universe particularly sharply just then.

Three lemons

Three cherries

Three plums

I'm losing my taste for fruit! ...

Des Moines was stacking the chips

Raking off the tables

Ringing the bandit's bells

This is a story that's a drag to tell

(In some ways)

Since I lost every dime

I laid on the line

But the cleaner from Des Moines

Could put a coin

In the door of a John

And get twenty for one

It's just luck!

Mingus also includes interludes that the album cover calls "raps" – five short sound clips of Charles Mingus talking and joking around with the session musicians. These can be unnecessary distractions or amusing insider views, depending on how you're listening. They were not planned. Sue Mingus made the session tapes available to Joni and she decided to pull out clips for the album. They are the last recordings Charles Mingus made.

|

| Inside Cover |

I had remembered this album being very badly received, and some bizarre accusations being hurled at Joni. When I look for that now, however, I find very little of it. Most of the reviews and features collected here on the jonimitchell.com are very positive.

I don't know if those stories just aren't online, or if I'm misremembering or unknowingly exaggerating what I read at the time.

What I remember is Joni accused of what is now called cultural appropriation: Joni was "trying to be black". She was trashed for being a jazz novice and dilettante – a kind of "how dare she" collaborate with a Jazz Great like Mingus.

These are just about the stupidest things you can say about a musician – about any artist – and even stupider when we consider that Mingus reached out to Joni, and not the other way around. (Although if she had reached out to him, or any other musician, there would be absolutely nothing wrong with that.)

There are many tributes to this album online, celebrating both its music and its lyrics. Cameron Crowe did this wonderful interview in Rolling Stone (I remember reading it in real time) (really, I do), and a few months later, the album was panned in the same venue.

The most idiotic critic comment I found was in a university newspaper. I normally don't trash novice writers, but the evidence here is too good to pass up. I'm also including it because it's typical of what I remember reading at the time.

I've nothing against an established artist trying to break away from the stuff they've already done so that they might "advance their art," but I protest against artsy experiments in areas where a particular artist has no business being.Yep, a guy in college is passing judgment on where Joni Mitchell "has business being".

Though the music and lyrics jell [sic] better this time than on her previous Don Juan's Reckless Daughter (a bottomless pit of amorphous atonalism and free-associative lyrics that expressed the forgettable in terms of the incomprehensible)...You just know he was dying to get this line in, something he thought of for the previous album and didn't get a chance to publish. I'll be generous and assume he would now find that line embarrassing.

The album cover

If you like Joni's painting, the Mingus cover art is a treat – four pieces on this one album.

On the front cover, there's an abstract expressionist painting, and if you look closely, you'll see a figure in a wheelchair (from behind), and a long-legged, female figure, sitting, possibly at a piano, her arm raised, hand on head. Interestingly, the painting is not the full cover. The painting is in the centre of the cover, framed by white space, with the album and artist's names above and below. This serves to make the cover more minimalist – which is what you'll find inside, music that is abstract and minimal.

Inside, there's an expressionist portrait of Mingus as big, clumsy, immobile, possibly paralyzed. But he also seems deified, like some of kind of ancient god descending from the heavens.

Also inside, there's another slightly abstract, slightly cubist portrait of Mingus, with Joni beside and behind him, smiling, but unseeing. It's a painted version of a lovely photo that you can see here.

On the back cover, Joni has painted Charles Mingus in his wheelchair, from behind, on a front porch or veranda with a sweeping view. It might be a sad and lonely picture, or perhaps just contemplative.

Cacti or stockings?

Naturally there are no cactus or stockings in this album, as the lyrics are not about Joni. I wonder, is the age of cacti and stockings behind us? Does she do that on any of the later albums? We shall see.

Now it can be told

David Yaffe, in Reckless Daughter: A Portrait of Joni Mitchell, revealed the genesis of the Mingus-Mitchell collaboration. This excerpt, published in Jazz Times, credits Sue Graham Mingus – Mingus's wife, a record producer, band manager, and former editor – with the idea. She was casting around for a fitting final project for Mingus, an outsize talent who was dying. It seems more marketing decision than a musician's desire to connect.

This bit has stayed with me.

When she first met Mingus, he was already in a wheelchair, facing the Hudson River. He had not yet lost his ability to provoke. "That song 'Paprika Plains,'" he told her. "The strings are out of tune." Mingus was testing Joni, but she adored him immediately and, of course, agreed with him about the strings on "Paprika Plains." She wished someone else had noticed. Illness had made Mingus vulnerable. He was sweet, but she saw the devil in him, too. Joni takes pride in her jive detector, and she knew she was in the presence of the real thing.Other musicians on this album

For the "other musicians" section on this album, I'm using Joni's own liner notes.

The first time I saw his face it shone up at me with a joyous mischief. I liked him immediately I had come to New York to hear six new songs he had written for me. I was honored! I was curious! It was as if I had been standing by a river – one toe in the water – feeling it out – and Charlie came by and pushed me in – "sink or swim" – him laughing at me dog paddling around in the currents of black classical music.

Time never ticked so loudly for me as it did this last year. I wanted Charlie to witness the project's completion. He heard every song but one – GOD MUST BE A BOOGIE MAN. I know it would have given him a chuckle. Inspired by the first four pages of his autobiography – Beneath The Underdog – on the night of our first meeting – it was the last to actually take form – two days after his death.

This was a difficult but challenging project. I was trying to please Charlie and still be true to myself. I cut each song three or four times. I was after something personal – something mutual – something indescribable. During these experimental recording dates, I had the opportunity to play with some great musicians. I would like to thanks them here – they helped me to search.

Eddie Gomez - Bass

John Guerin - Drums

Phil Woods - Alto Sax

Gerry Mulligan - Baritone Sax

Danny Richmond - Narration

Tony Williams - Drums

John McLaughlin - Guitar

Jan Hammer - Mini Moog

Stanley Clark - Bass

I would especially like to thank Jeremy Lubbock for helping me to overcome inertia. And thank you Daniel Senatore for introducing my music to Charlie. Thanks to everyone who played on the final sessions. These versions satisfy me. They are audio paintings.

Sue Graham-Mingus graciously gave me access to the tapes I have interspersed throughout the album. For me they add a pertinent resonance. They preserve fragments of a large and colorful soul.

Charles Mingus, a musical mystic, died in Mexico, January 5, 1979 at the age of 56. He was cremated the next day. That same day, 56 sperm whales beached themselves on the Mexican coastline and were removed by fire. These are the coincidences that thrill my imagination.

Sue, at his request – carried his ashes to India and finding a place at the source of the Ganges River, where it ran turquoise and glinting with large gold carp, released him, with flowers and prayers at the break of a new day.

Sue and the holy river

Will send you to the saints of jazz –

To Duke and Bird and Fats –

And any other saints you have.

Comments

Post a Comment